|

Waterford

City

Structure:

Latitude: 52º 16' North, Longitude 7º 7' West

The rocks which form the base

of the City all belong to the Palaeozoic Group: principally Ordovician

Shales, underlying some Sandstone on the North West, and crossed - East

of the centre of the City - by an Alluvial bank running N.E./S.W. At the cliffs on the North and

South banks of the River Suir, above Rice Bridge, inter-stratification

of sharply-folded Ordovician Slates and Sandstone conglomerates may be

clearly observed.

Position:

Waterford

city is situated on the river Suir [pronounced Shure] about seventeen miles from where the

river

enters the sea. The only thing that distinguishes this first abatement

is the inadequacy of the word 'situated'.

In design almost fanlike, practically the entire

city is built on the

south

bank of the river. The

"Old

town", now the business centre, clusters

behind the broad quay-front on a low-lying strip of land left behind by

a gentle loop of the river at this point. From this, the land rises sharply to the east and opposite to the

west while remaining level in between. The eastern slopes are almost entirely occupied by private

residential estates, while the western and southwestern prominences are

largely given over to local authority housing development. There are corresponding elevations on the north bank eastwards

towards Christendom and westwards towards Mount Misery.

It is from this

latter point—high above the Suir, upstream from the river

bridge—that the city and its setting may best be observed. Here, the heights on both sides of the Suir persist to the very

banks, with the result that the river courses for a short distance

between towering cliffs before emerging to sweep in one majestic reach

past the city. Where it

goes by Waterford, the Suir is as wide as the Thames at Westminster

Bridge, the Vistula at Warsaw or the Neva at St. Petersburg; it is three

times the width of the Tiber at Rome, the Seine at Paris or the

Mansanares at Madrid: and five times the width of the Liffey at

O'Connell Bridge.

It is not surprising

then that it is from the river that Waterford gets its civic character. From our observation point the spacious mile-long quays extend in

an unbroken line eastwards. The

broad quays of Waterford have attracted attention since they were opened

up to the present length 300 years ago by the Corporation. Behind the tall quayside buildings the city's steeples and

towers rise in picturesque irregularity presenting a picture typical of

the older towns, in which ground contours dictated the layout of the

earlier streets. This

gradually gives way to the more regular development of later years

fringing the city on all sides. Such

are the elements forming a city that the natives are reputed to be slow

to leave without a struggle.

But

history credits Waterford men with more attributes than a reluctance to

leave their native city. In

the middle of the 15th century the citizens were reported to be 'heedy

and wary in public affairs, slow in determining matters of weight, and

loving to look ere they leap.' The

Irish word 'faid-ceannnac' has been applied to them too. This has been translated ‘long-headed’ with more zeal than

accuracy; it really means far-sighted.' Charles I found the people of Waterford “endowed with good

learning and generous manners." A present day writer found in Waterford "an air of

quiet" and "a sense of proportion" and described the

people as being "undemonstrative" He added "they do

not lack intelligence or amiability, they just have them implicit."

This traditional

reticence and absence of flamboyance in the Waterford character has been

responsible for the phenomenon perhaps peculiar to Waterford, of the

occasional emergence before the citizenry of vociferous prophets having

their origin outside the bounds of the city.

Their aim has been to insinuate that their superiority over the

natives in all matters is in direct ratio to the relative degree of

clamour created by each; the which of course has no basis in fact and is

merely an optical—or more correctly—an acoustical illusion.

FOUNDATION:

OUTLINE OF DEVELOPMENT.

The foundation of Waterford is claimed in some quarters to have taken

place late in prehistoric times. Other

writers place the event about the middle of the second century. However, it is difficult to go along any distance with either

theory on the strength of the supporting evidence quoted. At any rate the antiquity of the place where Waterford now stands

cannot be traced with any satisfactory degree of certainty beyond about

850 A.D. when the site was occupied and fortified by Sitric the Dane.

The inhabitants of this part of Ireland in pre-Danish times were a

pastoral people moving from place to place with their flocks or else

given to hunting. They did

not build towns, unless we admit as towns the settlements that sometimes

sprang up in the neighbourhood of Monasteries.

They certainly did not build sea-ports, and it was as a sea-port

that Waterford had its beginning.

The Ostmen or Danes as they are more commonly called, persuaded by the

rigours of their own inhospitable clime, had taken to the high seas in

search of plunder. During

the first half of the ninth century the shores of south-east Ireland were

ravaged time after time by Danish expeditions, Ardmore and Lismore being

the subjects of a number of raids. At the outset, these bellicose incursions took place only during

the summer months, the raiders returning home with their spoils at the

onset of winter. About 853

A.D., however, Sitric, the Danish chieftain, settled at Waterford and

set up a fortified encampment. A number of factors influenced the choice

of the site. The place

provided a splendid anchorage. It

was the lowest point at which the river could at that time be forded. Above all, the site could easily be defended. It was protected on three sides by water; in front by the

Suir; on the east and at rear by St. John's River and the marshes

flanking it. St. John's

River did not then, as now, flow neatly between regular banks.

Rather, its tortuous and uncontained stream meandered over much

of the ground now occupied by Lombard Street, William Street, the

People's Park, Catherine Street, and Parnell Street, turning this entire

area into viscous

marshland. These marshes

also extended westwards round the back of the site of the old town. Only on the west itself were substantial fortifications

necessary. This was Waterford in its infancy, a Danish stronghold, subject to

constant harassment by the Irish outside the walls, who broke in on more

than one occasion to lay waste the foreign colony.

The next phase in the life of Waterford began on August 25th,

1170 when the town was taken by the Normans under Strongbow. The Normans had been casting eyes in this direction for some time

prior, until MacMurrough’s invitation gave them cause for coming. Henry II arrived in Waterford the following year to keep the

expeditionary chiefs in line and receive their homage. The next royal visitor, in 1185, was

prince John, who granted the city's first Charter in 1205 thus starting

City Government

in Waterford. He revisited the city as king in 1211.

Richard II, too, visited Waterford twice, first in 1394 and again

in 1399

In l487 the city refused to obey the

direction of the Earl of Kildare to recognise Lambert Simnel as king and

ten years later repulsed a second pretender, Perkin Warbeck. It was as a result of this latter engagement that Waterford

became known as the Urbs Intacta a title conferred by Henry II. Printing was introduced into Waterford in 1550, the first book

being printed in the city five years later.

It

was in 1588 that Duncannon was fortified as a precaution against Spanish

attacks along the coast, which were being experienced at the time

Waterford was occupied by Mountjoy in 1603 and visited by Rinuccini in

1648. The latter, in his

Report on the Affairs of Ireland sent to Pope Innocent X,

described Waterford as being "one of the only two Irish cities he would

place in the front rank for reverence to the Holy See." In l649, the

city was unsuccessfully besieged by Cromwell, but

was forced to surrender to his Deputy, Ireton, in the summer of the

following year. After the

Battle of the Boyne, both James and William came by Waterford, James on

his way to France and William returning to England. It was soon after this, about 1700, that the Huguenots came to

Waterford.

There

was no armed uprising in the neighbourhood as part of the 1798

rebellion, the probability of such being set aside by the defeat at

Wexford. There was,

however, considerable United Ireland activity in the city and district,

where secret recruitment had been going on apace. Among those arraigned for seditious activity at the time was the

toll collector of the then five-year-old wooden bridge.

In l826, Waterford returned Villiers Stuart to

parliament against the

opposition of Lord George Beresford, the outgoing candidate and powerful

landowner in the district. Stuart

was put forward by Daniel O'Connell's Catholic Association and O'Connell

personally led his campaign here. Though

not a Catholic himself, Stuart was a man of liberal views and his

election was an important step in the way to Catholic Emancipation which

came three years later.

The Great Faminc of 1846-48 made

itself felt in the city and the Corporation records of the period refer

to several money grants to relieve the distress of the people.

The fact that there were large quantities of rice in Waterford, saved

the city from the worst effects of disastrous shortage in their normal

food supply.

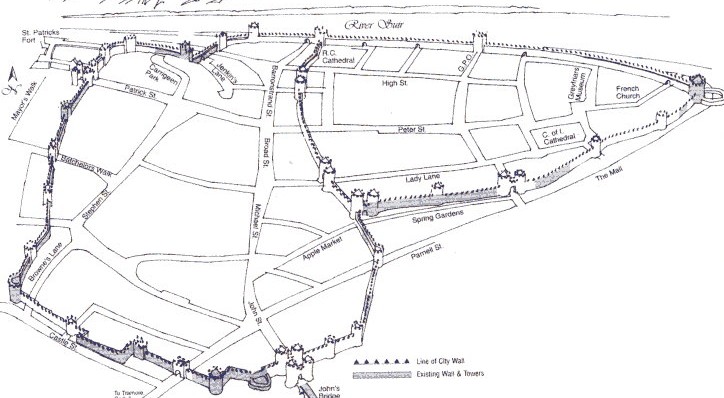

AREA

AND EXTENT: THE CITY WALLS.

There is no record of the extent of any settlement that may have existed

at Waterford prior to the middle of the 9th century. The Danish colony founded about that time (853 A.D.) was

triangular in shape and contained 15 acres approximately. This area was

enclosed by stout ramparts linking Reginald's Tower with St. Martin's

Castle (site in Spring Garden Alley); from thence running to Turgesius'

Tower, which stood in the immediate vicinity of the Allied Irish Bank

(corner of Barronstrand St.) and returning along the river-front to

Reginald's Tower.

Substantial remains of the wall in the 500 metre stretch between

Reginald's Tower and St. Martin's Castle still exist, except where

broken by the erection of the City Hall and the opening of Colbeck

Street (former (Colbeck Gate). These

traces may be observed between the houses of the Mall and Bailey's New

Street and, further up, between Spring Garden Alley and Lady Lane, about

12 metres back from the northern frontage of the former. In the old

handball alley, some four metres of the Wall—in places

six metres high—stand exposed. Also,

parts of the breastwork of St. Martin's Castle have been incorporated in

the foundations and lower courses of the buildings that now stand on its

former site.

There are

a few traces at the wall linking St. Martin's Castle with

Turgesius' Tower, and which followed the line of Michael Street and

Broad Street, about sixteen to twenty metres back from the present eastern

frontage of these streets.

The wall fronting the Quay has completely disappeared. It was demolished and the material thrown down to form the

foundation of the present Quays, partly under the Cromwellian

Commissioners in 1650 and totally by the Corporation of 1705, which

improved and enlarged the Quays.

- Extracted

from

Waterford, A Municipal Directory.

|